Why the US would lose Settlers of Catan

What Catan teaches us about comparative advantage and the benefits of trade

There’s been ample discourse as of late on tariffs and their negative impact. But what’s missing is the counterfactual: why trade is good in the first place —and it’s not just because of cheap goods.

So to think about why trade is good, let’s play some Catan.

Settlers of Catan is a strategy game where the first player to collect 10 victory points wins. Points are earned by deploying resources: grain, ore, brick, lumber, and sheep to build economies.

Each player starts with two settlements placed on resource-generating tiles, each marked with a number. When the dice rolls that number, you collect the corresponding resource. Tiles with higher-probability numbers (like 6 or 8) more reliably produce resources.

In other words, certain resources come easier to you than others. Each player therefore starts off with some form of comparative advantage.

If you’ve played Settlers of Catan, there’s always that player who refuses to trade. Their thinking: I’m playing to win so why would I engage in a transaction that benefits my opponent?

That player, often doesn’t win (even Napoleon) Why not? Because:

Self-sufficiency limits your consumption and production outcomes

Say I am a sheep queen. Sheep are my comparative advantage. This means that, given where my settlements are, it’s easier for me to produce sheep than other players.

Despite sheep being awesome, I cannot expand my empire with them alone. I need brick to build roads, lumber for homes, hay for cities. Even with an ore quarry settlement, it’s on low probability 2 tile. I’m not a productive ore producer. But I refuse to trade, so:

I go to the bank where the exchange rate is 4 sheep for 1 ore.

By trading, however, I might only need to trade 1 sheep for 1 ore, taking advantage of another players comparative advantage in hay. Yes, my opponent got the sheep they needed to build their next settlement, but I am also better off. To unlock favorable exchange rates, I could also build a settlement in a port city — Catan’s clear nod to trade’s power.

Not only is refusing to trade expensive, depleting my resources, but also makes me worse off as other players trade amongst themselves (sometimes specifically to spite the resource hoarder).

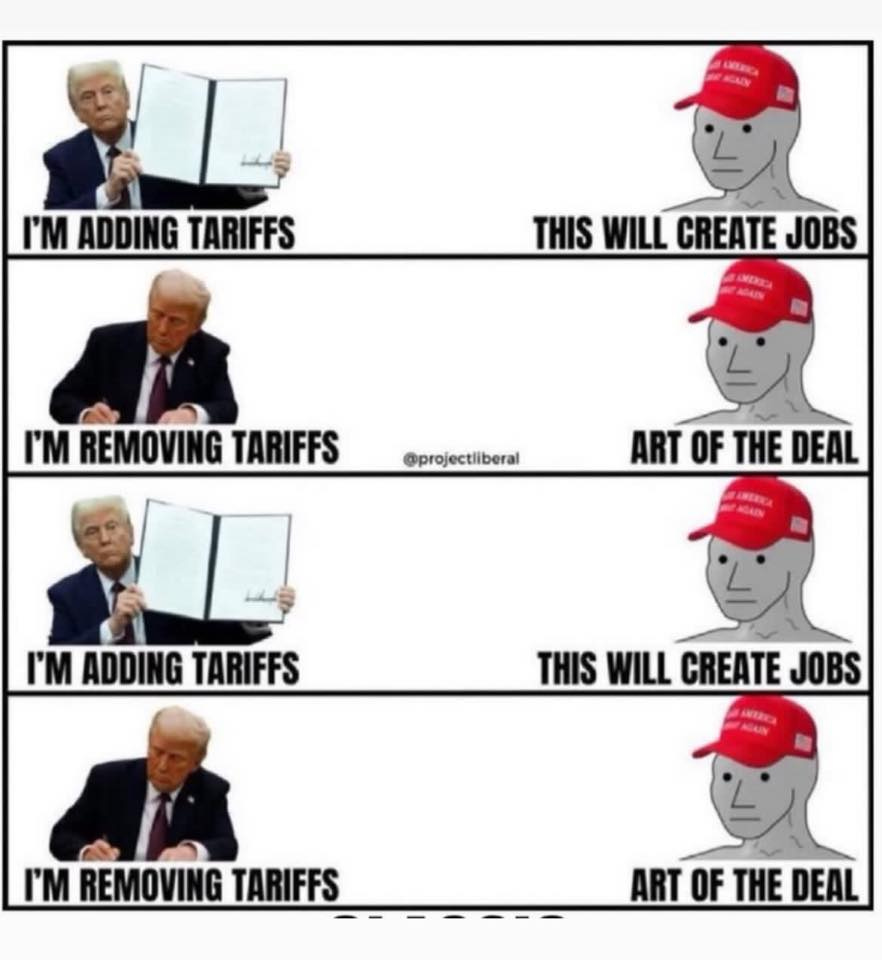

The same flawed logic of the resource hoarding player appears in real-world trade policy. “Liberation Day” has made official US’ shift from free trade principles. With sweeping tariffs announced, Trump is creating a more closed economy.

One could argue that the US has such a big and diverse economy, holding settlements in hay, sheep, ore, lumber, and brick, so we can stand to be a more closed economy.

Self-sufficiency, however, is costly.

And yes, costly in that tariffs increase prices. But much of the discourse overlooks the long-term cost — that of sacrificed productivity gains and long-term GDP growth.

With Trump’s tariffs, we are reverting to a self-sufficiency, diverting resources to lower value goods

Tariff’s impacted items are endless.

has an impressive piece featuring “real, live business owners, who make finished products that we interact with every day (not cold rolled steel).”But back to cold rolled steel, because The Wall Street Journal illustrates what much of the tariff commentary ignores:

“The latest tariffs cover a wider range of imports, including the screws, nails and bolts that serve as the connective tissue in manufacturing. That has set off a hunt to find domestic supplies of some of manufacturing’s smallest components. Manufacturing executives said the U.S. doesn’t have the plants to churn out the amount of steel wire or screws and other fasteners needed to displace imports. The production capacity we need doesn’t exist here in the U.S…”

Yes, screws from China are estimated to increase from 10 to 17 cents (this is pre 104% tariff or whatever it is now). But beyond the 70% price increase, what’s interesting here is that we are talking about a relatively simple item to manufacture, selling for (hopefully) less than a quarter.

So, if the US is to increase production capacity for wire, screws, and fasteners, that means our economy is diverting resources — labor, money for factories, etc. from producing high-value goods such as aerospace components and developing advanced technologies like semiconductor intellectual property.

That is the opportunity cost of self-sufficiency.

Because for every good or service an economy invests resources into producing, that means making a choice to not invest in something else.

Trump’s indiscriminate and unrelenting tariffs neglect such tradeoffs.

Trump:

"If you want your tariff rate to be zero, then you build your product right here in America."

With trade, the opportunity cost of not producing wires, screws, and fasters was low — we could cheaply import them. Without trade, the opportunity cost rises, as we scramble to meet domestic demand and make tradeoffs between investing in basic inputs or high-value goods and services.

To be clear, NVIDIA isn’t suddenly pivoting to nuts and bolts, but every economy faces finite resources — capital, labor, land, natural resources, limiting capacity. And if producing the “connective tissue of manufacturing” or any other heavily imported goods becomes a national priority, who’s to say semiconductors will always stay front and center?

And because our opportunity cost for producing screws is high, the price of domestically produced screws will also be high, even relative to tariffed imports. This is because domestic manufactures charge higher prices to justify using resources to make screws instead of higher-value products. American workers must also be paid enough to compensate for not working in higher-productivity sectors. These premiums directly increase domestic production costs.

Even then, supply is unlikely to meet domestic demand, adding price pressure.

Instead of focusing on products the US has a comparative advantage in, resources are diverted to meeting domestic demand, reducing efficiency

Not only is the opportunity cost of producing screws high but it limits our specialization, whereby we can further develop expertise in areas of comparative advantage for productivity gains. Total factor productivity (TFP) increases when the same unit of input generates more output and is key to sustained GDP growth.

That’s why genAI’s computing and reasoning power (e.g., the ability to solve problems and automate tasks) is such a big deal: it can drive TFP gains. But such gains require an ecosystem of investment — capital (e.g., facilities, machinery), labor, higher education (RIP), and R&D, resources that, in a closed economy, might otherwise be diverted to lower-value production (like making screws).

In Catan, TFP increases when I upgrade my settlement to a city. For each dice roll corresponding with my tile number, I now produce double that resource (i.e., increased output from the same input). Developing cities and increasing productivity happens much faster when, rather than relying on unpredictable dice rolls to gather everything I need, I leverage my comparative advantage to trade.

The result is a virtuous cycle: higher productivity means more resources, which enables more trade, which fuels even more growth.

Specialization based on comparative advantage creates additional value that wouldn't exist without trade, making trading partners better off

For the US, trade freed up resources for manufacturing specialization. The productivity gains that followed, as The New York Times reminds us, made it possible to shift to knowledge work and advanced technologies requiring a highly skilled workforce:

“…sometimes nations do not want to get stuck producing low-tech products when they could move up the ladder. The towns north of Boston dominated the country’s shoe industry throughout the 1800s; today they are better known for software startups, law firms and some of the nation’s most expensive real estate.”

Much like an economy evolves from producing simple goods to advanced products, early in Catan, I need roads and settlements — basic infrastructure. As my economy develops, I then shift to higher-value investments such as cities and development cards.

Thanks to trade and productivity gains, I'm no longer just a sheep queen. I'm a lumber liege, a brick baron, an ore overlord.

Similarly, as our trading partners focus on advancing their comparative advantage, they also increase productivity and evolve their economies. We then become more valuable trading partners to each other, with more sophisticated goods and resources to exchange (vs. hoarding because of protectionist induced scarcity).

Trade isn't zero-sum

Refusing to trade, whether in a board game or through protectionist policies, limits growth, increases costs, and diverts resources from areas of strength to less efficient uses. By embracing trade and specialization, we unlock the power of comparative advantage, driving innovation, productivity, and economic progress for players involved.

In Catan, as in global trade, the players who understand that mutual benefit isn't a sign of weakness but a path to prosperity are often the ones who build the most robust economies and ultimately win. The US has held the lion's share of victory points for decades, but with our playbook now drastically changing, we risk not only higher prices for consumers and businesses, but also ceding strategic advantages as other nations form alliances and trading partnerships without us.

In both competitive arenas, self-sufficiency might feel like the power move but it's rarely the winning strategy

Daily episode that, in addition to illuminating the detrimental effects of tariffs on small businesses, illustrates that essence of comparative advantage: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/14/podcasts/the-daily/trump-tariff-small-business-busy-baby.html?

"It’s just none of it makes damn sense. My husband’s a farmer. We grow corn and soybeans. He’s out planting today. Minnesota is really good at growing crops. We have great soil.

We have intelligent farmers. We have great equipment. China is really, really good at manufacturing. I love my team in China. We send each other gifts. They send me videos.

They love making my products. We have a great relationship. I would love for every country to do what it is best at and be able to thrive on what they’re good at. I honestly don’t think that we can bring manufacturing to the US and be good at it. We already have a hard enough time with the businesses that are currently here finding good workers. Who’s going to work in these factories?"

I love love love reading your pieces! Always so informative and you break down the concepts in such a good way!